Why is Japan's Population Shrinking So Fast?

And Is It Really a Crisis?

For those who sometimes prefer to listen rather than read, all my episodes are available as podcasts. You’ll find the links you need on THIS page.

For an all-singing, all-dancing video version of this week’s essay:

My eldest child was born in Japan back at the start of 2009. Two memories linger from those early days of life. One was him wrapped in a white towel, half asleep, slowly opening his eyes to look at me as a little fist poked out from under the fabric and fingers slowly unfolded. Beautiful - until I saw that one finger was unfolding faster than the others. The middle finger. I remember thinking at the time that this might be a portent of how our relationship would pan out.

My other memory is pleasant surprise at being gifted 10,000 yen by the Japanese government for adding a new person to the population. That’s about £50. Not the kind of money that keeps a newborn in nappies and formula for very long, but while my baby was flipping me the bird at least Japan’s leaders were playing nice.

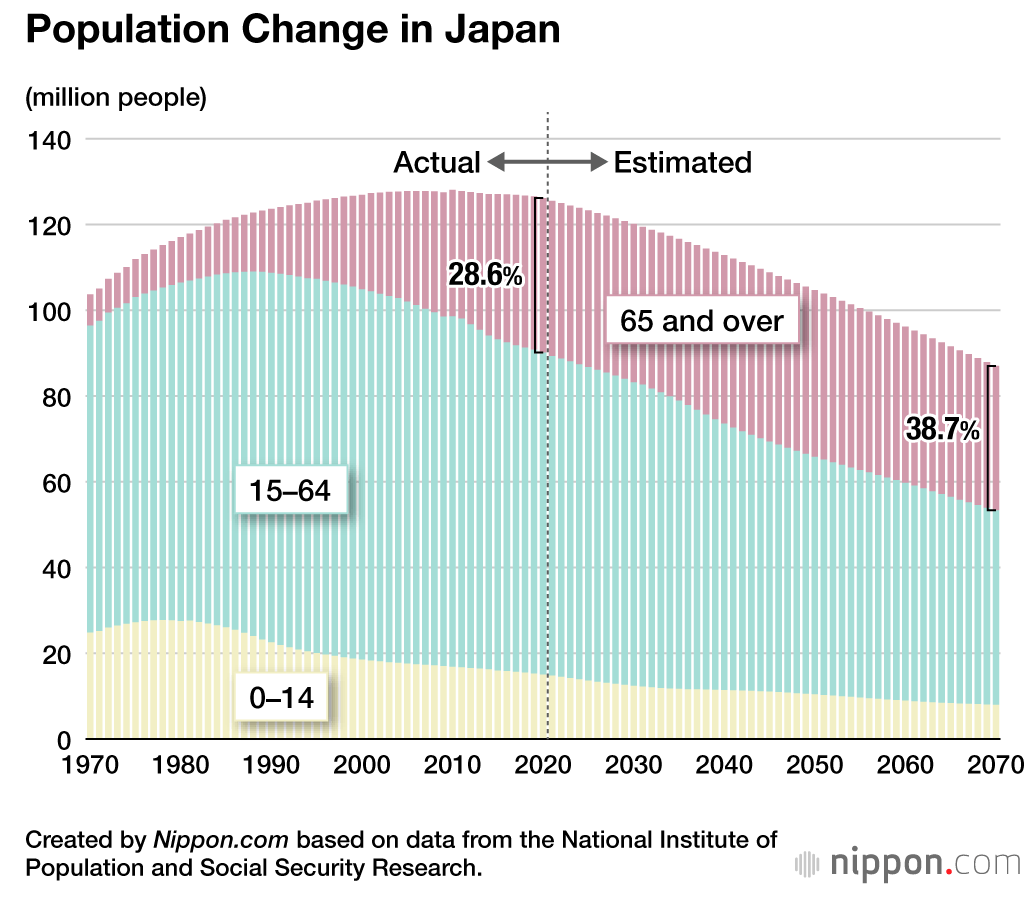

The context, of course, was a population decline which, in the years since I pocketed my 10,000 yen and promptly left the country, has become a genuine crisis. The gap between annual births and deaths in Japan now stands at around 900,000, with some predictions suggesting it will soon top a million. Within around a decade, population decline will become irreversible.

Compounding the problem, a third of Japanese will soon be over the age of 65. Most are not in work and many require expensive and labour-intensive care on top of pensions. Japan’s national debt, meanwhile, is somewhere around 260% of GDP. Unlike many other countries, most of that debt is held within Japan, making it a less serious problem. Still, it is a very large number and it limits the government’s room for manoeuvre.

So how did Japan get here? And can anything be done?

Japan is reaping the results of a process of urbanization which began a century ago but picked up pace soon after the end of World War II. All around the world, where people begin moving into cities in large numbers the birth rate tends to decline. Such are the pressures of work hours, living costs and the lack of family members nearby to help out with children. Japan has been no exception.

The second major reason is that young people in Japan have vastly-reduced employment prospects compared with their parents’ generation: a legacy of the country’s economic woes stretching back to the 1990s.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, most men who made it into a decent-sized company were more or less guaranteed a job for life. The old ‘salaryman’ cliché encompassed both long working hours and the shunting of underperforming employees around a company rather than sacking them. That world has gone but there remains the expectation that men will be the primary breadwinners in a family. Where young men feel that their prospects are poor, they simply won’t take the risk of getting married and having children.

Salarymen in Tokyo. The long-term prospects have gone but the expectations (and sober clothing) remains.

Problem number three: successive governments across the last 10 to 15 years have tried and largely failed to make it possible for women to re-enter career-level jobs after they have children. Many must make do with part-time, casual roles, making it less attractive to have children. Women in double-income households who do re-enter full-time jobs find themselves doing disproportionately more housework and childcare compared with their husbands. This ‘double burden’ problem is yet another reason why women choose not to become mothers.

The childcare facilities required to change this situation are meanwhile expensive and - children being children - noisy. Neighbourhood protests have been known to break out when plans emerge for a new nursery.

Finally, there’s evidence that women’s expectations in life are changing but government policy is failing to keep up. Japan’s new Prime Minister, Takaichi Sanae, is amongst those opposed to allowing married couples to keep separate surnames, in a country where in practice the husband’s surname is almost always adopted. This is starting to put women off getting married - which matters because research suggests that it is people choosing to delay or forego marriage, rather than marital fertility, that is the real driver of population decline.

Kindergarten children in Japan. Well behaved now but there will be noise later…

What can be done? All sorts of things are currently being tried:

Pay people to have children, via grants, subsidies and tax allowances. Japan currently spends less on this than countries like the UK, France and Australia.

Establish more childcare facilities, though the problems remain both of neighbourhood opposition and a shortage of staff (in a broadly comparable sector, nursing, just one person currently applies for every four jobs advertised).

Push companies to tackle the work-life balance problem. Prime Minister Takaichi is reportedly in favour of encouraging companies to build childcare facilities on their premises.

Make urban housing more affordable.

Culture change, towards men doing more childcare. Earlier this year, Japan’s baseball superstar, Shōhei Ōtani, became a father (‘Papatani’) and took parental leave. The hope is that he might contribute to a culture shift, in a country where uptake of paternity leave is already rising steadily - now standing at a little over 30%, a figure comparable to the UK. Others suggest that Japan’s politicians need to enact policies to force a more radical shift - this is unlikely under the socially conservative Takaichi.

Encourage older people to remain in or re-enter the workforce. Japan is currently doing quite well at this, with around 40% of Japanese companies hiring people over the age of 70. This frees up the labour market, to allow for more generous parental leave, while combatting the epidemic of loneliness seen in aging societies.

Robots! I covered this in a recent essay, where I predicted a shift towards ‘co-bots’ capable of augmenting human capacities rather than replacing us. As with employing more elderly people, the aim is to tackle labour market shortages to the point where more generous parental leave arrangements become sustainable.

Migrants! Both as an immediate boost to the workforce and to the future population: 3% of babies born in Japan are now born to non-Japanese couples. A political hot potato, amidst the rise of the populist right in Japan. I’m going to revisit this thorny question early next year, but policy under Japan’s current leadership looks likely to become, if anything, tighter.

Another way of tackling Japan’s population problem is to say, simply, that it isn’t really a problem after all. We may currently be living through the steepest phase of Japan’s population decline, as the baby-boom generation departs the scene.

After that, things may not look so bad. Some of the most prosperous countries on earth - the likes of Switzerland, for example - manage very well with small populations. Japan would struggle to raise an enormous army, if such were ever to be required again. But most current evidence points to the automation of war: Japan needs to churn out drones, not children.

On some of the slightly less pessimistic predictions, Japan’s population may stand at around 80 million by 2100. That sounds very small compared to its current level of 124 million, but it’s not much smaller than the population was in 1950, before the boom.

One possible future scenario is that Japan’s leaders, keen to avoid radical and divisive discussions about forging a multi-cultural society, talk less about ‘solving’ the population crisis and more about transitioning to a smaller society. If that society is peaceful and becomes steadily more productive, then a few generations from now people might find themselves asking: ‘Crisis, what crisis?’

—

Image Credits

Population Decline: Nippon.com (fair use).

Salarymen in Tokyo: Picryl.

Kindergarten in Japan: Picryl.

Thanks for this. In my case my employer (a private uni) was able to offer… 12.5% of my usual salary for paternity leave. Thankfully I didn’t have to rely on that, but if that’s what they’re offering, is it any wonder more men don’t take paternity leave? This is an n of 1 mind you.

Great article- the last part sums up something even some of my far right leading ‘friends’ agree with- we need to transition to a less consumerist and convenience led society which will not need to keep growing its population, ( and then would not need foreigners to supplement the workforce! :)..