'Sanamania,' the Japanese Right and the CIA

Last weekend, Japan’s first female prime minister, Takaichi Sanae, won herself a landslide in a snap election to her country’s powerful lower house. She and her coalition partners now enjoy a ‘super-majority,’ meaning they can pass legislation even if the upper house tries to oppose it.

It remains to be seen what Takaichi will do with all this power, but it’s striking that while most pollsters and pundits thought this would be the most unpredictable election in years, one organisation apparently knew better.

From pretty much the moment Takaichi called her election, rumours circulated on social media that America’s Central Intelligence Agency was predicting a Takaichi landslide and was trying to work out how to play it to US advantage.

Whatever the truth of those rumours, it should come as no surprise that the CIA might have a keen grasp of Japanese politics. Since the end of the Second World War, the CIA has been more than just an interested observer of Japanese politics. It has actively helped to shape it, providing money and assistance to some of its biggest - and most notorious - players.

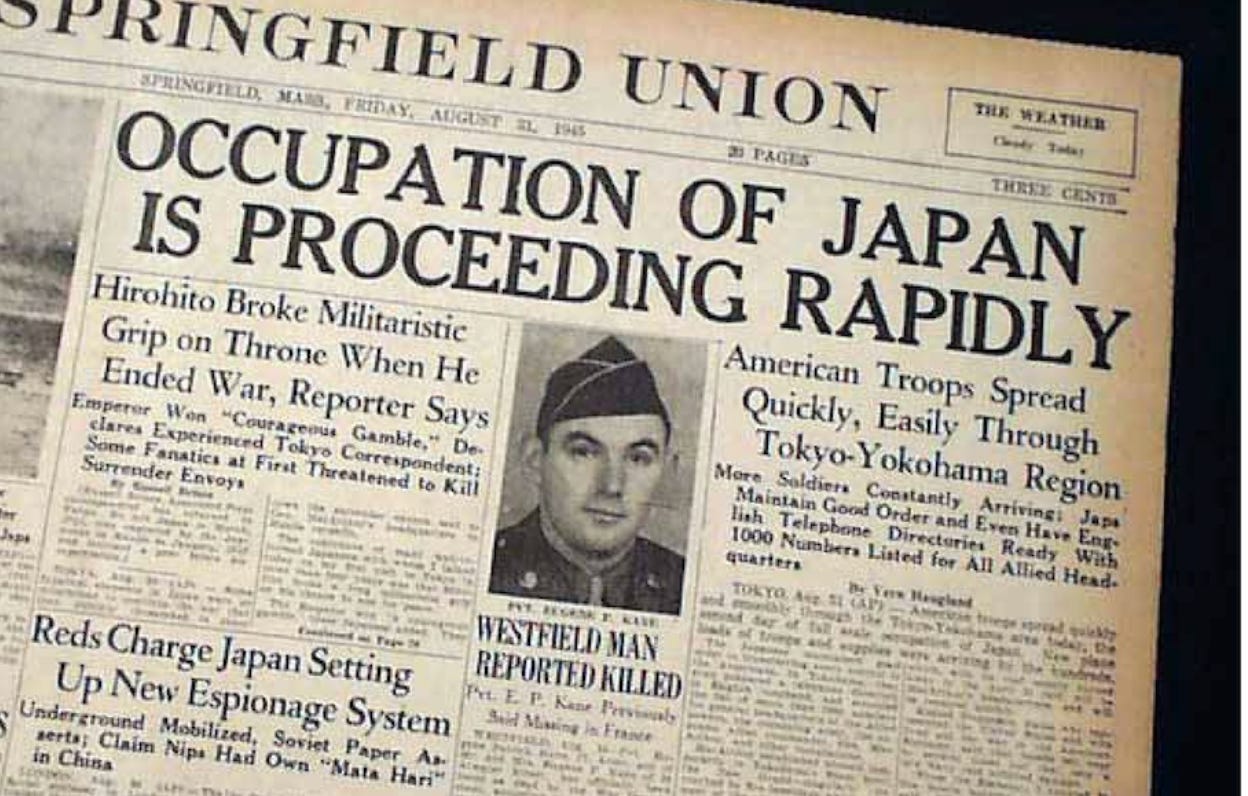

To understand why the CIA took the interest that it did in Japanese politics, we need to go back to the heady early days of the Allied Occupation of Japan, which began in the late summer of 1945 and was led by the United States. Idealistic young Americans set to work in Japan building a liberal paradise, only for the calculus to change as tensions rose with the Soviet Union and the prospect loomed of China falling to Communism.

What America now needed in Japan was a robustly conservative ally, one that would be sympathetic to its foreign policy aims, provide bases for its troops and buy its exports. Ambitious American wheat producers even hoped to wean the Japanese off rice and onto bread – sparking conspiracy theories, raised once again last year by the populist right-wing party Sanseito - about Americans trying to weaken the Japanese by separating them from their staple.

One of the most controversial moves made by the Americans in this period, known as the ‘reverse course,’ was to rehabilitate ultraconservative politicians and political fixers who had been expected to serve long stints in prison – or even to face execution.

One of the most notorious was Kodama Yoshio, about whom I wrote a few months back: a gangster who made a fortune in China during World War II, supplying essential raw materials to the Imperial Japanese Navy. Of particular value to American intelligence after the war was his network of friends and informants within the Chinese Communist Party and their Nationalist rivals.

Kodama was released from Sugamo Prison in Tokyo in December 1948 – the day after Japan’s wartime prime minister Tōjō Hideki was hanged there. He began helping the CIA with their anti-Communist work in East Asia, and collaborating with them in the creation of a new conservative party in 1955: the Liberal Democratic Party or LDP, which under Sanae Takaichi has just secured a landslide election win.

In truth, Japan was moving in a conservative direction anyway, by the end of the 1940s. One of the great social injustices which fuelled support for Socialism and Communism was the large number of Japanese farmers who, at war’s end, still worked their land as tenants. Occupation-era reforms changed all that, making landowners of millions of Japanese overnight. It was one of the largest peaceful redistributions of land in history.

Having secured their ownership rights, in a country that would always need rice and fresh produce, Japanese farmers became a reliable vote-bank for the LDP.

Still, declassified records show that the CIA did what it could to help Japan’s nascent conservative party on its way across the 1950s and 1960s – much as it did Italy’s centre-right Christian Democrats. Operatives based in the US embassy in Tokyo, and others working outside it, spent millions of dollars supporting the LDP, largely in the form of cash contributions to election expenses:

(Foreign Relations of the United States 1964-68 XXIX Part 2)

The CIA believed that Japan’s Socialists were receiving help from Moscow. So they did what they could to infiltrate the party, along with the student groups and labour unions that were affiliated to it.

Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party is said to have pleaded with the United States not to release these documents, given the reputational risk to them in Japan - the LDP has always maintained that it received no support from the CIA.

What did the CIA get for their money? The LDP’s unimpeded stewardship of a trade-friendly economy stands out, as does its dogged support for American military bases on Japanese soil – particularly in parts of the country such as Okinawa, where local opposition has been fierce.

The best-known casualty of that loyalty to America was Kishi Nobusuke, a suspected war criminal who was released from prison the same day as Kodama and who went on to become prime minister.

So controversial were Kishi’s tactics in crushing opposition to the renewal of Japan’s Security Treaty with the US in 1960 – hiring Kodama and his thugs to secure the streets; barring entry to Japan’s parliament for members who opposed him – that he was eventually forced to resign.

Above: protests in 1960 against the renewal of Japan’s Security Treaty with the United States

Below: Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke at the signing ceremony for the renewed Security Treaty at the White House

The LDP has also toed America’s line on China, over the years: freezing its relations with Mao’s Communists, thawing them after Nixon made his famous visit in 1972, and now sticking closely to America’s position on Taiwan. LDP politicians are meanwhile thought to have funnelled information about Japanese politics – and especially the Left – back to the CIA.

Advocates of CIA involvement in Japanese politics argue that it gave it the unity of purpose required to build a strong and prosperous country. Critics point out that for much of the past 80 years, Japan has looked like a one-party state - and a corrupt one at that.

A culture of exchanging cash for influence set in, causing scandal whenever Japanese politicians were caught drawing on secret slush funds or taking bribes. In the most colourful cases, stories appeared in the Japanese media about people wheeling around shopping trolleys filled with cash, or having their homes raided and stacks of cash and gold bars discovered.

In recent years, Japan’s economic woes have hurt the LDP’s dominance. Opposition parties, especially on the centre-left, have begun to do better. And yet thanks to Sanae Takaichi’s extraordinary personal popularity - with fans buying up her famous black leather handbag and pink pens during the recent election – her party, steeped in Cold War politics and covert operations, is now riding high once more.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this essay, please take a moment to like and share.

—

Image credits

1960 protests: MIT Visualizing Cultures (fair use).

Kishi Nobusuke: Japan Times (fair use).

Sanae Takaichi: NBC News (fair use).