The Gangster

The Allied Occupation of Japan - Part II

Part I, ‘The Blue-Eyed Shōgun’, is HERE.

This Deep Dive post is currently free to read and share.

When the Asia-Pacific war ended and the Occupation began, the vast majority of Japanese looked back on a conflict that had brought only disaster: death, hunger, trauma and destruction on a truly epic scale.

For a handful of opportunists, however, the war had been a nice little earner.

One of them was Kodama Yoshio, born in 1911 to a former samurai family in Japan’s northern Fukushima prefecture: one of the poorest parts of the country, where some families were forced to sell daughters into slave-like conditions in factories or into prostitution.

Growing up between Fukushima and Seoul in Japanese-occupied Korea, where he lived with his sister and worked in a steel mill, Kodama’s childhood was a potent brew of poverty, injustice, ultranationalism and wide reading in the social sciences. These last might sound like the innocent entry on the list. But they were deeply political in Japan in the early 20th century, concerned with the way modern Japan was developing and whether and how it ought to change course.

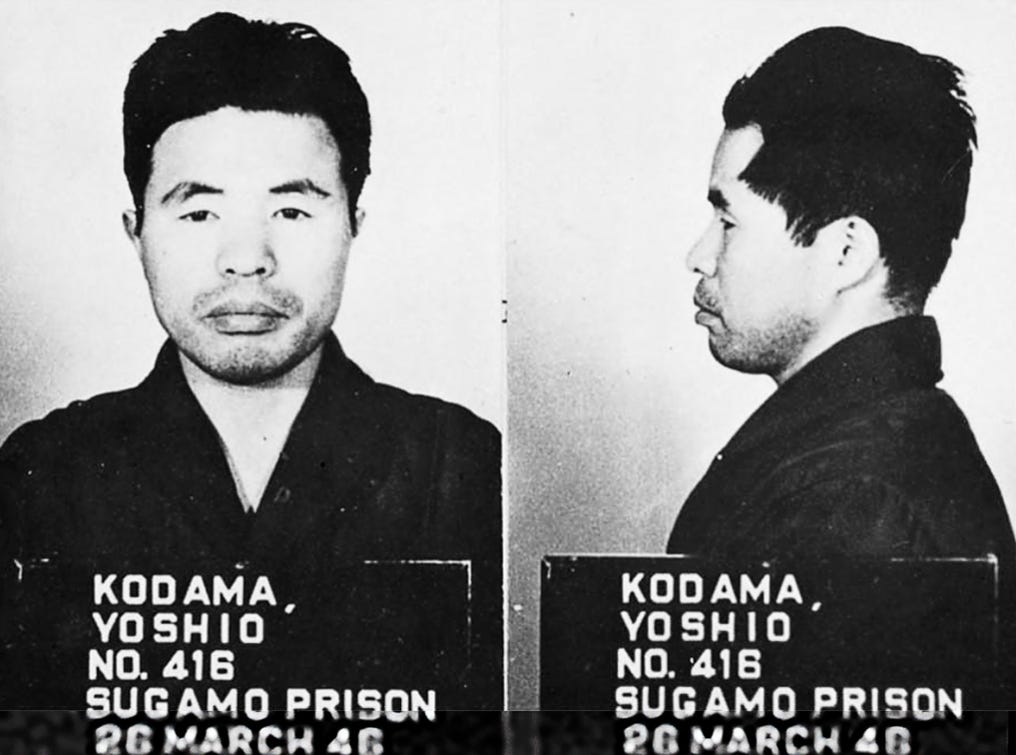

The first sign of where these early life experiences were taking Kodama came in 1929, when he was arrested and imprisoned for trying to present a petition to the Emperor for the relief of the poor. It was the first of many stints behind bars for Kodama, the most notable of which began during the early months of the Occupation, when he found himself amongst a group of suspected Class-A war criminals imprisoned at Sugamo in Tokyo.

What had Kodama done to earn this attention from the Occupation authorities?

To keep reading, please consider signing up as a paid subscriber for £3.50 per month (or £30 for the year) - or email me if you’d like a gift subscription for a month. You’ll find a short intro to the benefits of my paid tier in my first Occupation post. Paid subscribers also have access to podcast versions of these posts.

MacArthur was keen to round up and purge from public life people who had in some way assisted Japan's militarists during the war. Many tens of thousands of people were duly forced from their jobs as policemen, teachers, journalists and businessmen.

Kodama had made himself a prime candidate for purging by joining, in the 1930s, a tradition that went back to the late 19th century: ultranationalists and gangsters - the overlap was considerable - who served Japanese interests in mainland Asia through espionage, covert political activity (sometimes disguised as merchants or monks), the gathering of precious industrial resources and even assassination.

Bearing the romantic nickname ‘continental adventurers’, these people served in organizations like the Gen’yōsha (Dark Ocean Society) and the Kokuryūkai (Black Dragon Society), wielded considerable influence in China, Korea and Russia and maintained intimate links with the Japanese military and top politicians.

Kodama also spent the 1930s contributing to a period of domestic violence in Japan so extreme that commentators started describing the country’s politics as ‘government by assassination.’ Victims included two prime ministers, a former finance minister, a prominent businessman and a governor of the Bank of Japan. Kodama was not involved in any of these high-profile killings, but was suspected of plotting other assassinations and ended up spending most of the period between 1932 and 1937 behind bars.

Kodama’s spell in prison was rumoured to have been eased and shortened by well-placed contacts who shared his ultranationalist leanings. Some of these were in government, meaning that upon release Kodama was able to walk into a job with Japanese foreign intelligence. His role was to promote the country’s interests in China, with whom all-out war began in 1937, via a new organization carrying the appropriately abstract and innocent-sounding name of ‘China Problems Settlement National League.’

On his regular trips to wartime China, including Japanese-occupied Shanghai, Kodama helped procure essential raw materials for the Imperial Japanese Navy, including radium, nickel, cobalt and copper. He made friends amongst China’s Communists, Nationalists and black marketeers, and developed an intelligence network featuring hundreds of criminals, thugs and members of the Japanese Military Police.

Kodama’s failure, in 1942, to win himself a seat in the Japanese Diet was no doubt a deep disappointment to him. But he could console himself with a fortune that by August 1945 ran to around $175 million in diamonds, platinum and cash - to which he soon added by looting Imperial Japanese Army stores. These stores, comprising food, weapons, cash and more, had been put together in anticipation of a fight to the death, defending the Japanese homeland from the Allies. That fight having failed to transpire, the likes of Kodama took what they could get their hands on and put it on the black market.

Better still, Kodama’s contact book included members of the Imperial family. That meant that at war’s end, when he was forced to bid farewell to the Chinese mines, fisheries and munitions plants that he controlled, Kodama was able to take up a post on the Advisory Council to Prince Higashikuni: the only member of the Japanese royal family ever to have served as prime minister.

Higashikuni did not, of course, have terribly much real power. He took up the post on 17th August 1945, two days after surrender and barely a fortnight before the Occupation began in earnest. Nor did he last long in the job. In October 1945, Higashikuni resigned as prime minister after clashing with MacArthur over the latter’s determination to repeal Japan’s ‘Peace Preservation Law.’

Here was a sign of the low opinion in which the Occupation would later be held by Japanese conservatives. In their view, the 1925 Peace Preservation Law was a much-needed bulwark against Communism, all the more so at a time when people in Japan were reeling from the hardships of the war and might be tempted by left-wing ideologies. Higashikuni felt strongly enough about the law to resign in protest. At 54 days, his remains the shortest tenure of any prime minister in Japanese history.

Two months after Higashikuni’s resignation, Kodama’s fortunes changed for the worse, too, when he was arrested and imprisoned at Sugamo. Prison was hard. But it was also a networking opportunity. Alongside reading the newspaper and writing a bestselling memoir (I Was Defeated), Kodama spent time playing board games with Kishi Nobusuke, who had served in the late 1930s as the highest-ranking bureaucrat in Manchukuo (and whose grandson, Abe Shinzō, would go on to become Japan’s longest-serving Prime Minister in the early twenty-first century).

Kishi’s less savoury activities in Manchukuo had run to money-laundering, corralling millions of Chinese – from the unemployed through to captured POWs – into industrial slave labour, consorting with drug-traffickers and yakuza, and making the most of his power over those around him to feed a legendary libido.

But across 1948, prewar ultranationalism and criminality became increasingly intertwined with postwar Japanese conservatism and a rightward shift in US Occupation policy. With the onset of the Cold War, America came to regard Japan less as a liberal experiment than a future regional ally. That meant a reliably conservative politics, a strong economy for the sake of US-Japan trade and even a degree of rearmament.

Kishi was an early beneficiary of this shift, released without trial on 24 December 1948 - the day after Tōjō Hideki was hanged there. Kishi drove straight to the prime minister’s residence, where his brother Satō Eisaku – a future prime minister, currently serving as Chief Cabinet Secretary – helped him to change out of his prison uniform and into a business suit. ‘Strange, isn’t it,’ Kishi commented, ‘we’re all democrats now.’ Less than a decade later, Kishi himself was prime minister.

Kishi Nobusuke pictured with a young Abe Shinzō

Released the same day as Kishi, Kodama picked up where he had left off, seeking to influence Japanese politics from behind the scenes. 1945 - 48 had been prime years for the Occupation’s liberal agenda: army disbanded, war criminals tried, new Constitution promulgated, conglomerates broken up. But at the same time, the seeds were being sown of a more conservative future Japan.

In addition to a conservative shift in American policy towards Japan, known as the ‘reverse course’, ran the consequences of one of the Occupation’s most important reforms. This was the introduction, in 1947, of quotas for the amount of land that any one person might legally own or lease. The rest was bought up at low rates and sold to the people who had been tilling it, via long-term mortgages whose burdens were soon eased by inflation.

Before the war, half of Japan’s land had been tilled by tenants. By 1949, that figure had plummeted to just 10%. The large numbers of Japanese who now owned their own land were far less likely than their forebears to be interested in Socialism and Communism. Instead, they were a ready-made voting bloc for a future conservative party.

A fascinating range of people and organizations proved to be interested in forming and steering such a party. They included Kodama, who ploughed some of his wealth into the creation of a new political party called Nihon Jiyūtō (Japan Liberal Party). He remained friends with its leader, Hatoyama Ichirō, during his time inside Sugamo.

Kodama remained subject to a purge until the end of the Occupation in April 1952, keeping him officially out of public life. But this suited him well. He had spent much of the prewar and wartime period in a shadowy existence, between Japan and mainland Asia. Now he became one of Japan’s most important postwar practitioners of kuromaku politics: the word means ‘black curtain’ and refers to the stagehands on a kabuki theatre stage, who control the action taking place out front.

One of the other major players behind that curtain was US intelligence. Kodama is thought to have offered his services first of all to Charles Willoughby, MacArthur’s chief intelligence officer, who was well used to dealing with unpleasant characters in the pursuit of American interests. Those interests involved, first and foremost, combatting Communism in places like China. Kodama had more experience than most in dealing with China’s Communists, so both he and what remained of his intelligence network in the country became prized assets.

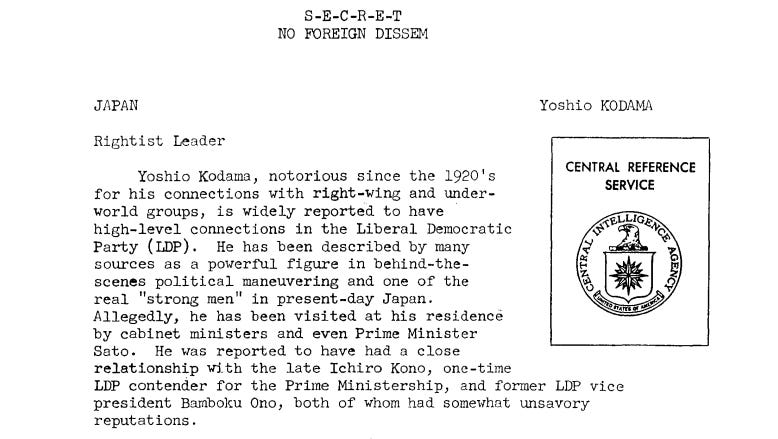

Extract from a CIA file on Kodama Yoshio, dated 1969.

The CIA eventually fell out of love with Kodama, having discovered to their cost that he was more committed to the cause of building his wealth and power in Japan than he was to fighting Communism in Asia. By that time, however, the Occupation had ended and Kodama had helped bring into being one of the most successful political parties in world history. The Liberal Democratic Party, a coalition of Japanese conservative forces, has rarely been out of power since its formation in 1955.

Ordinary people in Japan would soon tire of gangsterism and corruption in their politics. But for a while, in the latter part of the Occupation, there was an alignment of sorts between US policy, conservatism, ultranationalism and the self-interest of people like Kodama. These were years, for all their shadowy elements, during which democracy as an ideal made a spectacular come-back in Japan.

Nor was this just about politics. It was a condition of new-found freedom that coloured the arts and popular culture, too. In the third of these five essays on the Occupation, available next month, I’ll look into this world of the ‘new Japan’ through the life of one of its greatest names, Misora Hibari: child-star, undisputed queen of Enka and controversial symbol both of the liberty and the Americanization of culture that the Occupation brought to Japan.

—

Images

Kodama Yoshio, mugshot taken in Sugamo Prison: Wikipedia (public domain).

Kishi Nobusuke and Abe Shinzō: Picryl (public domain).