Why Oda Nobunaga Welcomed the West

Japan's Three Unifiers & the Western World - Part I

One of the great myths about Japan is that for more than two centuries, beginning in the 1630s under the Tokugawa shogunate, it closed itself off from contact with the outside world.

It became, people say, a sleepy and mildly xenophobic hermit kingdom - until it was woken up and dragged back into the global community in the 1850s, by the American Commodore Matthew C. Perry and his gunboats.

The truth is more interesting. Rather than blocking foreign contact, Japan’s leaders filtered it, largely through the great southern port of Nagasaki. This included maintaining important ties with Korea, China and the Dutch. When it came to the wider Western world, Japan’s ‘three great unifiers’ - credited with steadily reuniting a divided country across the late 1500s and early 1600s - took radically different views.

In this post, I’ll begin with the first of those unifiers: Oda Nobunaga, a man who regularly tops votes of favourite historical figures in Japan. Later, I’ll introduce his successors: the brilliant but slightly deranged Toyotomi Hideyoshi and the supremely strategic Tokugawa Ieyasu, founding father of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Oda Nobunaga (1534 - 1582) rose to power in Japan in the 1560s. He’s credited with helping bring to an end the Sengoku Jidai or ‘era of warring states.’ Japan at this point was a patchwork quilt of feuding domains, with no central authority.

Kyoto was home to a revered yet largely powerless duo: the Emperor and the Shōgun. Nobunaga made both of them his puppets, marching his troops into Japan’s ‘eternal city’ in October 1568 as part of his quest to bring the whole country under his personal control.

A house divided: Sengoku Japan’s patchwork quilt of domains

Portuguese merchants and missionaries had been plying their trades in Japan for more than twenty years by this point. But Nobunaga was too powerful, and the Portuguese too weak and few in number, for there to be worries about Europeans invading or colonising Japan.

Instead, Nobunaga became an early adopter of Portuguese technology. He adapted firearms for use on Japanese battlefields, practicing his own shooting every day. He’s credited - though some question the claim - with developing a technique of firing in ranks, so that his soldiers could keep up a steady volley of gunfire despite the time needed to reload.

An arquebus, of the kind imported into Japan in the mid-1500s

Nobunaga also developed an early modern bromance with one of the most important Jesuit missionaries of the age: Lúis Froís. In the spring of 1569, the two of them sat down together on the drawbridge of a castle that Nobunaga was building in Kyoto.

The ‘Demon King,’ as he later became known, was still far from conquering all of Japan at this point. And yet as the rising star of the era he had received a begging letter from the impoverished Emperor and was finding warlords from around the country starting to copy his bizarre sense of fashion - including a tiger-skin worn around the waist.

Froís quickly discovered that Nobunaga had no use for religion. As Froís put it:

He despises the gods, the Buddhas, and all other idols… he openly declares that there is no creator of the universe, no immortality of the soul, or life after death.

To Nobunaga, Europeans were simply an unthreatening source of taxable trading profits and intelligence about the wider world - Nobunaga quizzed Fróis extensively about China and India when they met. They were not an existential threat to Japan - that role was being played, as far as Nobunaga was concerned, by wealthy and powerful Buddhist sects who opposed his rise to power. Some of them were armed to the teeth. Warrior monks defended temple-fortresses. Buddhist laypeople doubled as guerrillas.

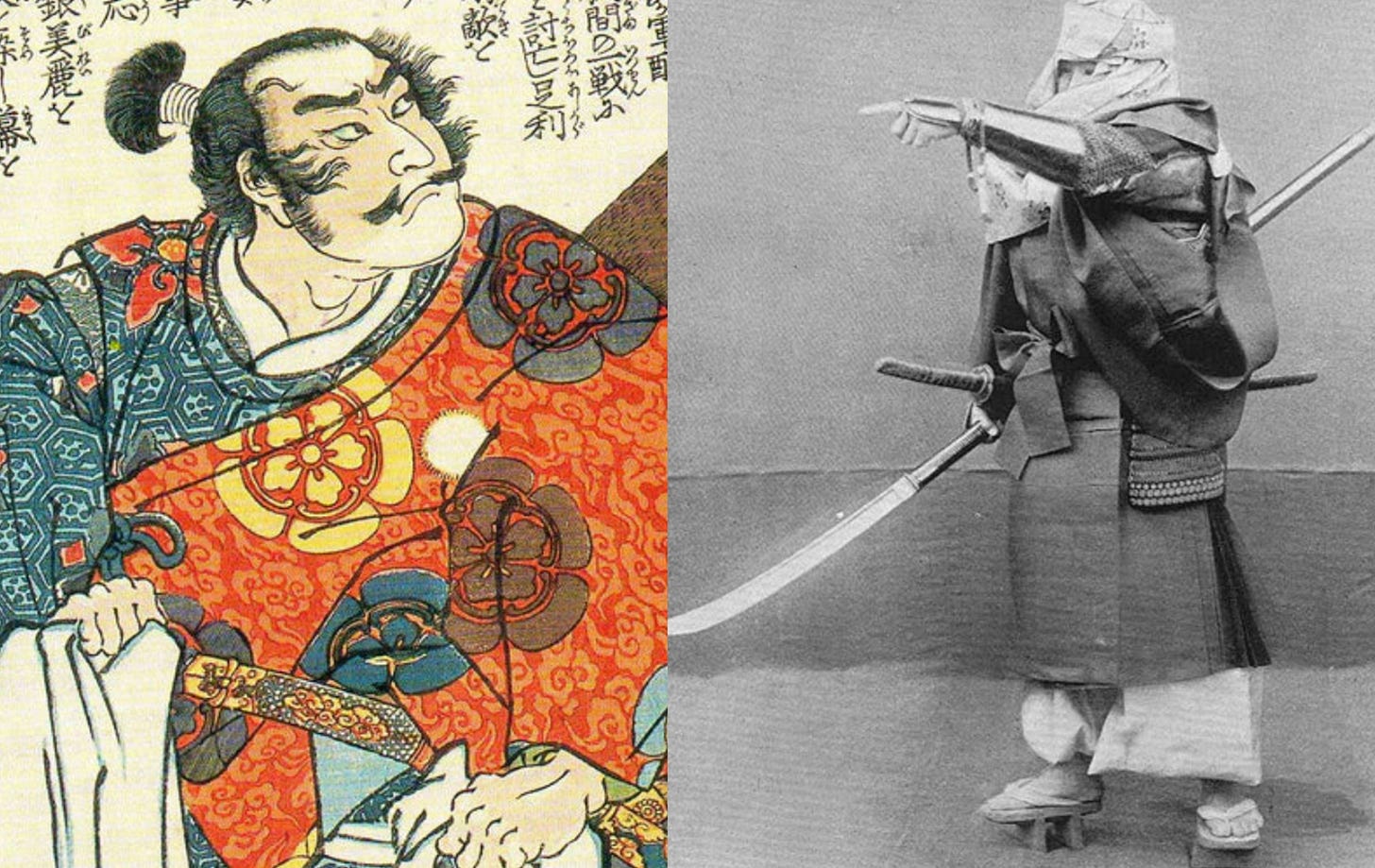

Oda Nobunaga and a ‘warrior monk’ (modern photographic reconstruction)

For the Jesuits, too, Japan’s Buddhists represented Enemy Number 1. Its priests, they argued, peddled lies about paradise while privately believing that the cosmos comes from and returns to nothing.

This, thought the Jesuits, explained Buddhist priests’ love of silent meditation and gardening. The former was a flight from sadness and guilty consciences. The latter was a forlorn attempt at finding beauty in a finite world.

Fróis hoped that Nobunaga would one day be persuaded of the truth of Christianity. For now, he was content to have found an ally in the fight against Buddhism - one who could go beyond preaching its evils and actually confront it with swords, pikes and guns.

Jesuit missionaries in their trademark black robes. Detail from a Japanese folding screen

In September 1571, Nobunaga sent tens of thousands of troops to slaughter and burn their way up the Tendai sect’s home base of Mount Hiei, just outside Kyoto. They killed thousands of people, laid waste to countless temples and works of art, and finished off Tendai as a force in Japanese politics. According to Fróis’s account, nothing remained on the mountain save a carpet of ash across which only badgers and foxes moved.

Nearly a decade later, Nobunaga vanquished his other great Buddhist enemy: the Jōdo Shinshū sect, at what is now Osaka. Through a combination of siege, starvation and extraordinary violence against its pop-up armies of ordinary men and women, he brought the sect to its knees. The patriarch was forced to surrender his temple-fortress - though his son burned it down before Nobunaga had the chance to make a triumphal entry.

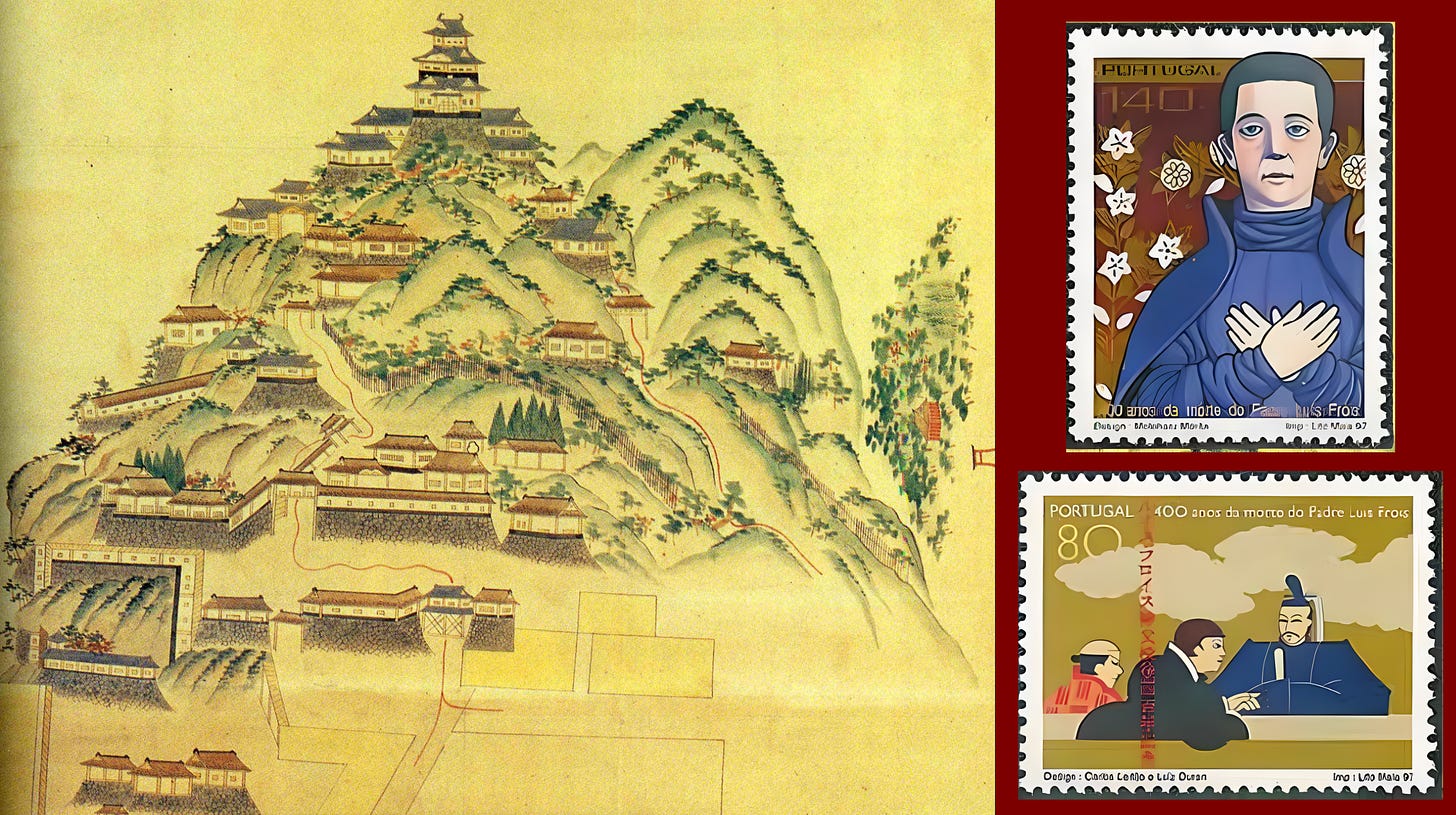

A friendship of convenience between Froís and Nobunaga continued down the years. Nobunaga invited Froís to stay at his magnificent castle in Gifu: one of the architectural marvels of the era, built atop a mountain. And he intervened on the side of Froís and his fellow Jesuits when a debate with some Buddhists - encouraged by Nobunaga, to weaken the Buddhist grip on his countrymen’s imaginations - threatened to turn violent.

Left: Gifu Castle. Right: Portuguese stamps marking the 400th anniversary of the death of Luís Froís (1597 / 1997)

Nobunaga never fulfilled his dream of conquering all of Japan. In the summer of 1582, he suffered a betrayal at the hands of one of his own generals and was attacked at a temple called Honnō-ji, in Kyoto.

Fróis was living just one street away at the time, getting ready to say an early morning Mass when he heard gunshots and saw a fire break out. He didn’t witness the drama that ensued, but later drew together an account of what had transpired.

Nobunaga, Fróis discovered, was wounded early in the fight. He fought on regardless but was forced to retreat to a backroom. There he died, or perhaps took his own life, while the temple burned down around him.

Oda Nobunaga’s fiery demise

Froís was either fickle in his friendships or belatedly appalled at the level of violence - including against innocent women, men and children - with which Nobunaga had become synonymous by the time of his death.

As Europeans in Japan found themselves on the cusp of having to deal with a brand-new leader, Hideyoshi Toyotomi, Froís penned a sort of anti-eulogy for his one-time friend, Nobunaga:

There remained not a strand of hair, nor bone, nor anything but be turned to dust and ashes… his memory vanished with a thud, and he instantly descended into Hell.

—

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please like and share.

Japan and the World is a reader-supported publication, so if you’re in a position to do so, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you!

I’ve just discovered your posts. They strike me as excellent, both in terms of depth but also in their wide range. Much foreign interest in Japan focuses narrowly on specialty fields: business, food, ikebana, manga, etc. I look forward to your next posts.