Rise of the Right - Free to read version

Who Are Japan’s New Breakthrough Parties - And What Do They Want?

If you were in Japan, or into Japan, in the 1990s and 2000s, you’ll remember talk of the country’s lost decade(s) and their toll on young Japanese in particular. The media, in Japan and abroad, brimmed with catastrophizing categories and buzzwords to describe a generation who were mentally checking out of society:

Freeters drifting in casual, part-time employment.

Parasite singles: sponging off their parents while indulging a taste for high-end consumerism.

Hikikomori shut themselves away in their rooms for months, even years on end (at home we refer to my wife’s sanity-preserving alone-time from our children as Hikikomummy).

Niito, with origins in the British acronym NEET, were people not in education, employment or training.

Sōshokukei-danshi: ‘herbivorous men’, refining hobbies or personal grooming at the expense of relationships or work.

I may be doing someone a disservice, but I don’t recall any commentators at the time suggesting that when these young people grew up, they would contribution to a revolution in politics. If someone did, then good on them: it appears to be happening.

For anyone new to Japan’s politics, here’s the headline: up until recently, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) ruled the roost. Rarely out of power since its formation in 1955 - for reasons that I’ll explore in my next Occupation post, later this month - the LDP became synonymous with machine politics. It was well-organised and well-networked, clever at keeping its base happy. It served as an umbrella for a wide range of political views and policy positions. For most aspiring politicians in Japan, the question was not which party to join but which faction of the LDP to align yourself with.

That began to change in the 1990s, when the truly epic scale of corruption in the LDP combined with the end of Japan’s high-growth years to cause voters finally to lose patience. Even then, the LDP managed mostly to cling on to power, thanks to two things in particular: coalition agreements with Kōmeitō (a party originally affiliated with the Buddhist Sōka Gakkai organization) and the apparent desire of Japan’s opposition to emulate the People’s Front of Judaea scene in Monty Python’s Life of Brian.

Former PM Tanaka Kakuei (left) and senior LDP figure Kanemaru (‘The Don’) Shin (right) infuriated the Japanese public when stories came out of enormous amounts of corrupt cash changing hands - sometimes from the backs of limousines, sometimes wheeled around in shopping trolleys…

The result was confusing and - dare I say? - a bit boring. Years ago, I would no more have developed a love of Japan based on its politics than I would based on - dare I say? - Japanese pop.

That is now changing.

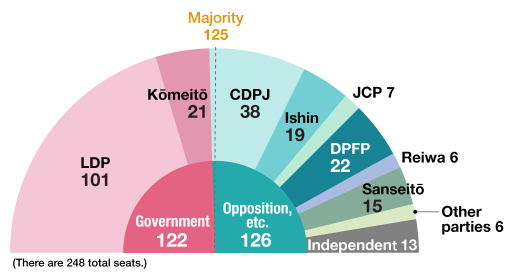

For the first time ever, after this summer’s Upper House elections in Japan, the LDP-Kōmeitō coalition has a majority in neither the upper nor the lower house of Japan’s parliament. Prime Minister Ishiba has faced calls to resign, including from within his own LDP party. He is so far refusing.

** UPDATE: on Monday 8th Sept, Ishiba announced his resignation **

So what’s going on in Japan?

The answer: more and more Japanese are deciding they have had enough of:

Stagnant wages

High taxes (your car alone costs you four separate kinds of tax: buying it, owning it, how heavy it is, and keeping it on the road - amounting to a higher tax burden on cars than in countries like the UK)

Expensive essentials, including rice

And - in some cases - foreigners

In my experience, xenophobia in Japan sometimes dovetails with a gentler, more understandable anxiety that non-Japanese people won’t know how to behave. The country’s famous omotenashi hospitality culture and high levels of social trust rely on people treating others with respect and kindness. It’s beautiful, and many western commentators wish for something like it. But it’s also fragile.

That sense of the fragility of Japan’s social contract is political dynamite: as a genuine voter concern and as something to which aspiring political parties can and do make powerful rhetorical appeal.

Who are these new parties?

Here’s where we get into the real story: the rise of two very different parties that could redefine Japanese politics. To keep reading, please consider signing up as a paid subscriber for £3.50 per month (or £30 for the year) - or email me if you’d like a gift subscription for a month. You’ll find a short intro to the benefits of my paid tier in last week’s post.

From the top six parties in Japan’s Upper House, following this summer’s elections, take away the LDP, Kōmeitō, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (the country’s main opposition party) and the Osaka-based Nippon Ishin no Kai - and you’re left with two big winners.

Together, they inflicted historic losses on the LDP-Kōmeitō coalition and got people, inside and outside Japan, talking about the rise of a new Right.

The more moderate of the two is the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP), which managed to quadruple its representation and become the third-largest party in the Upper House.

Led by Tamaki Yūichirō, a man with impeccable political credentials - University of Tokyo, JFK School of Government, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs - the DPFP’s policy agenda resonates with a lot of people under 50:

Supporting workers and raising take-home pay by reducing taxes

Preserving Japan’s pacifist stance but strengthening anti-espionage measures and potentially clarifying the role of the Self-Defence Forces (a perennial issue in Japanese politics)

Encouraging Japan’s domestic defence industry, to reduce reliance on the US

Regulating the acquisition of land by non-Japanese. They are in favour of integration rather than exclusion when it comes to non-Japanese (they used to have a more strident policy, but walked it back under criticism)

Increasing investment in education

Supporting cryptocurrency, AI and financial tech, returning Japanese tech companies to the top tier globally after decades of losing out to Silicon Valley

Tamaki Yūichirō out on the campaign trail

Sanseitō have a similar voter base to the DPFP (though Sanseitō skew male). But they’re an entirely different proposition…

Led by a former teacher, shop manager and LDP member named Kamiya Sōhei, they emerged largely online and rose to prominence during COVID - since which time they’ve been accused of peddling conspiracy theories about the pandemic and about a ‘deep state’ in Japan.

Kamiya appears to have learned a lot about populist politics from Donald Trump in the US, though he doesn’t think Trump’s personal style is a good fit for Japanese politics.

Kamiya Sōhei, leader of Sanseitō

‘Sanseitō’ means ‘Participate in Politics’ and their policy platform is tied up with the rhetoric of ‘Japanese First’:

Resisting ’globalism’ and capping the number of foreign residents in Japan. Establishing rules for how non-Japanese integrate, including the amount of money received in social security benefits

Kamiya has insisted he’s not xenophobic, despite talk of a ‘silent invasion’ of foreigners and the prevalence of anti-Chinese rhetoric amongst his supporters. He says he just wants clarity and controls

Robotics, AI and automation over large-scale immigration, as a way of tackling Japan’s demographic crises

This appears to dove-tail with concerns in Japan about over-tourism and tourists behaving badly - a topic mired in misinformation, but with the occasional regrettable truth to it:

A Chilean influencer filmed herself doing pull-ups on a torii gate. She later apologised after a huge outcry.

Opposition to same-sex marriage and LGBTQI+ rights

Replacing Japan’s constitution. A common complaint on Japan’s right is that its existing constitution was created under American auspices, and not in Japan’s interests. Sanseitō’s proposals for a new constitution range from restoring the Emperor’s authority as head of state and ending Japan’s pacifist stance to removing citizens’ rights, establishing controls over the media and returning education to the patriotic tone of the past

Reportedly in favour of nuclear power and nuclear weapons, for economic and strategic security

Greater food self-sufficiency for Japan (as an aspect of restored sovereignty). But a firm ‘no’ to wheat, which Sanseitō have claimed is harmful to health and was part of the damaging Occupation period (in reality, wheat was part of emergency food aid to Japan after war’s end). Sanseitō’s stance was mocked during the recent election - see below

Increased welfare - for Japanese citizens only

Communist Party leader Tomoko Tamura holds up a piece of melonpan bread, at a campaign event during the recent election.

On paper, the DPFP look like becoming the more influential of these two breakthrough parties, with a pragmatic focus on education, tech and the cost of living.

But what may matter more in the end is the capacity of Sanseitō to push Japanese politics as a whole rightward - as commentators suggest has happened in the UK with figures like Nigel Farage. At the same time, Mary Harrington wrote in UnHerd recently about Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ creating a ‘permission structure’ that helps similar ideas to do well abroad. That appears now to apply to Japan.

A second possible outcome is that Japan’s political parties will increasingly embrace digital politics, after Sanseitō’s proven success with it. Less talked-about after these recent elections - and a subject for a future essay - is an up-and-coming party called Team Mirai (literally ‘Team Future’), whose leader, an AI engineer named Anno Takahiro, gained a seat in the Upper House this summer.

Harder to place on the political spectrum than the DPFP and Sanseitō, Team Mirai are developing ideas for technology-driven governance in Japan, fighting the stereotype of a country that looks hyper-modern in some ways while still harbouring a love of fax machines.

Whether or not you like the direction of travel, Japanese politics just became interesting again.

*

That’s all for this instalment of Japan Now. Do please hit ‘Like’ if you’ve enjoyed it…

If you’re a paid subscriber, really I cannot thank you enough for your support.

If you’ve read this via a 7-day trial or gift subscription, thank you for giving me a chance to prove to you that a subscription might be worth your while. I hope I’m there, or nearly there, in convincing you!

Image credits

Tanaka Kakuei: Wikipedia (Creative Commons).

Kanemaru Shin: Wikipedia (Creative Commons).

Upper House election graphic: Nippon.com (fair use).

Tamaki Yūichirō out on the campaign trail: The Economist (fair use).

Kamiya Sōhei: Wikipedia (Creative Commons).

Chilean influencer: Instagram (anonymised).

Tomoko Tamura: Streamable (fair use).