Can Vending Machines Save Japan?

Part I: Trust meets High Technology

Why is it that some of Japan’s most futuristic-looking tech actually comes from the 1960s and 70s?

Exhibit A: the shinkansen. I challenge you to stand on the platform, watch it cruise to a halt in front of you - while remaining behind the yellow line of course, or else the station announcer will scold you - and not feel a little shiver travel down your spine.

Here it is, at its launch in 1964 and earlier this summer. Not all that different…

Exhibit B: Japan’s ubiquitous vending machines, or jidōhanbaiki.

The country is estimated to be home to around 4 million: around one machine for every thirty people.

Twenty years (and about twenty kilograms of body mass) ago, I remember visiting Japan and thinking these things were absolutely amazing. Yes, we sort of had them in the UK. If you paid your money and then banged on them and pleaded with them, they might eventually allow a packet of crisps or a chocolate bar to drop into the collection tray.

But in Japan: all these gleaming boxes! All this choice! Hot and cold drinks, of course. But also ramen, live crabs, edible insects, whale meat, batteries, canned bread, fresh flowers, umbrellas - and those hollow plastic spheres containing small toys that my children love and then immediately lose.

Have I missed anything? Let me know in the comments…

If you were inclined to believe the British media back in the 1990s and 2000s, most of these vending machines in fact dispensed knickers, which were - shall we say - ‘pre-loved’. That was back when ‘Japan’ in the western imagination was mostly cool, crazy or creepy.

We’ve moved on since then - but Japanese vending machine tech is still reassuringly unchanged:

Left: yours truly experimenting with a vending machine 20 years ago.

Right: a brand-new one at Osaka Expo 2025.

There have been a few changes over the past couple of decades. Fewer cash payments. More facial recognition, helping to keep cigarettes out of young hands. Plus machines equipped with seismic sensors, allowing them to dispense their contents for free in the event of a disaster.

But in the coming years, machines like these are set to do much, much more. And - here’s my prediction - it’s going to be all about trust. Trust between people, and trust between people and machines. I think it’s no exaggeration to say that Japan’s future hinges on both.

In Part I of this two-part series, I’m going to explore how we got to where we are: how trust and technology combined to produce the vending machines that visitors love and residents of Japan rely on. In Part II, I’m going to look at what’s coming.

Trust is where all this began. Japan has long been home to a mujin hanbai tradition: ‘personless selling.’ The earliest example I’m aware of - let me know below if you have others - is the okigusuri (‘placed medicine’) of the Edo period.

From the late 1600s, an itinerant apothecary might turn up at your home, pay his respects at your family altar, have a chat with you and then leave a medicine chest behind, full of herbal preparations, eye-drops and amulets. He trusted that when he returned a few months later, you’d pay for what you’d used and return the rest.

Statue of an itinerant apothecary in Toyama, the home of okigusuri in early modern Japan. Plus a child, who looks like he might be hassling him for sweets (or else performing a guitar solo - it’s not a very clear image…).

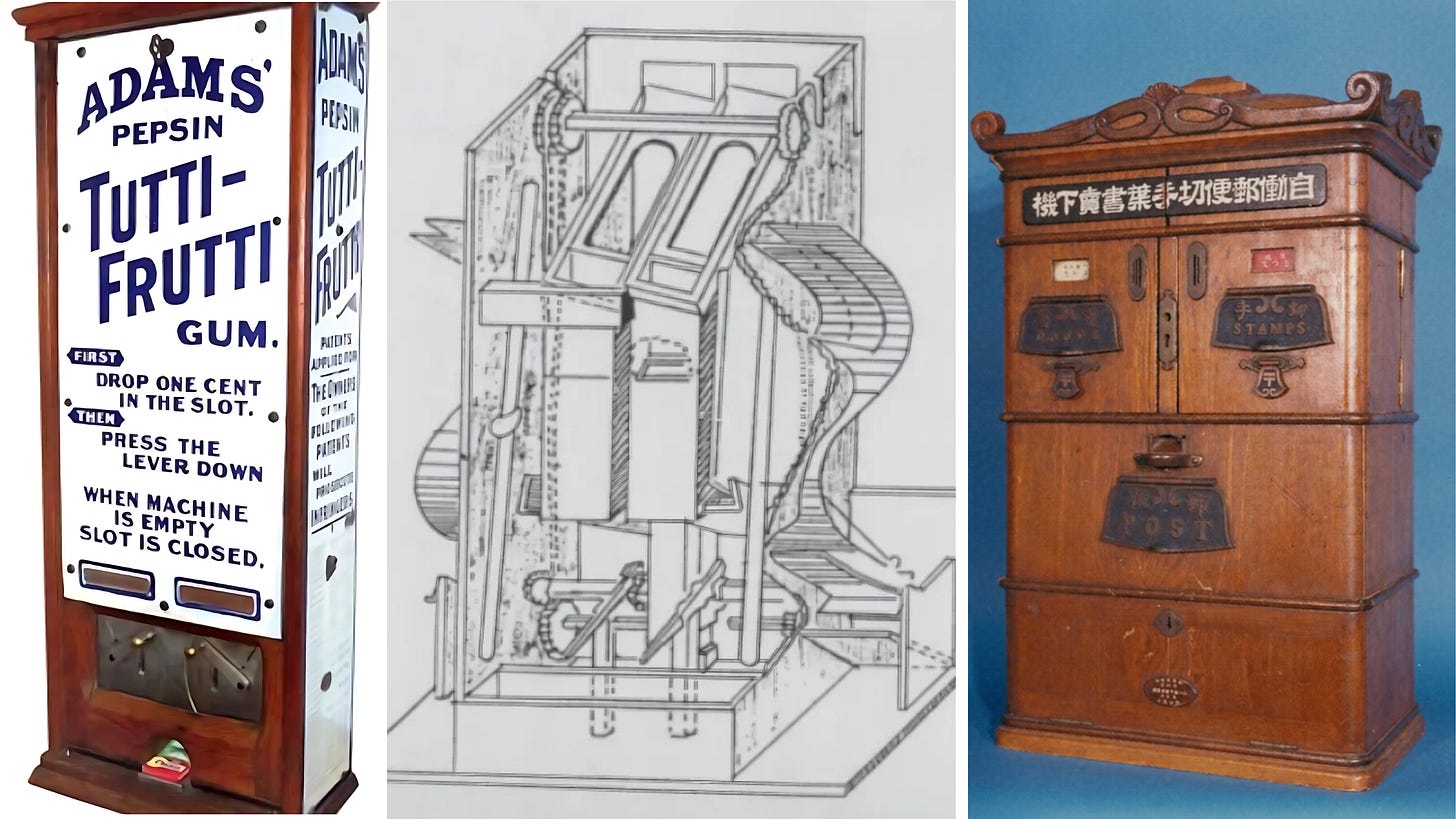

Soon after the Meiji Restoration, technology and mujin hanbai started to come together in Japan, shaped by contacts with the West. The earliest known vending machine patent was granted in Britain all the way back in 1857, for a stamp-selling machine. But the first working machines only appeared in the 1880s, with Tutti Frutti chewing gum sold from them on railway platforms in New York City.

That same year, Takashichi Tawaraya filed a patent in Japan for a tobacco vending machine, including in his application a drawing showing how the machine could work. Tawaraya wasn’t prepared to invest unlimited trust in his clientele: his patent included a mechanism for rejecting counterfeit coins.

The same was true of the first known vending machine to actually be produced in Japan, in 1904: a postcard and stamp dispenser, designed by Tawaraya. Validation was by coin size: coins that were too large wouldn’t fit, and coins that were too small would slip through the mechanism and be ejected.

There followed, across the next three decades, machines selling tobacco, milk, sake and also sweets - some of which would play a little jingle when young customers inserted their money. Production stopped during the war but began again in the 1950s with machines selling chilled juice and train tickets.

Everything changed from the late 1950s, with the re-minting of Japan’s coins and Coca-Cola’s entry into the market. The American drinks giant soon began installing tens of thousands of its own machines in Japan every year and offering pre-bottled drinks - rather than the old squirt of juice into a paper cup.

Cans followed from the mid-1960s and a raft of laws were passed to strengthen consumer trust, covering everything from the temperatures at which drinks would be dispensed to the sterilization of components. Hot canned drinks became available in 1972 and plastic ‘PET’ bottles arrived ten years later.

From left to right: the NYC Tutti Frutti machine; Tawaraya’s first patent; Japan’s first-known vending machine, selling postage stamps and postcards.

There have been bumps along the way. Some users considered it demeaning to have to effectively bow when picking up drinks from the bottom of a vending machine. They complained and manufacturers responded with internal ‘endless belt’ technology, capable of carrying drinks up to the top of the machine. But this took about 2 or 3 seconds - yielding still more complaints.

As an aside, I suspect that omotenashi culture in Japan - its legendary hospitality and the easy lives to which customers feel entitled - is at least partly the result of a rich tradition of complaining. If you don’t believe me, try an experiment:

Go onto Google Maps and choose an area of Tokyo.

Search for convenience stores in that area.

See how many - if any - have a rating higher than about 3.6 stars.

Perhaps it’s a virtuous circle: complaining → better service → higher expectations → more complaining.

Readers living in Japan: do you see customers complaining a lot - and does it get results?

As Japan began to get more visitors, from the 1990s onwards, the chances of foreign coins being used in vending machines increased. This was a problem. The Iranian 50-rial coin was similar in dimension to the 500-yen coin and yet was worth a hundred times less. Korea’s 500-won coin was also similar to Japan’s 500-yen coin, and was little more than a tenth of its value. It was slightly heavier, but all you had to do was drill a hole in the middle and it would work in a vending machine.

Japanese manufacturers had to put in some serious graft to keep the system afloat. Electromagnetic validation was used for coins, while bills/notes were scanned for size, the magnetic properties of their ink and their optical patterns. With more than 30,000 counterfeit notes detected in Japan in 2004 alone, the risk to vending machine viability was not to be taken lightly.

Brute-force attempts to open up what the Japanese media sometimes called ‘roadside money-boxes’ peaked in the late 1990s, with 222,000 incidents reported between 1996 and 1999 alone. This is worth remembering the next time you encounter social media claims that this sort of thing never happened in Japan before all the migrants and tourists started turning up…

More serious was a spate of killings that occurred in Japan back in 1985. A company launched a campaign giving people a free health drink when they purchased something from a vending machine. For some customers, this was just an annoyance so they left the drink on top of or near the machine. Someone laced a number of these bottles with a herbicide called Paraquat, fatal to humans. Eleven people died, and their killer has never been found.

Despite all these problems, vending machines have survived to become one of the signature sights of modern Japan, bringing added colour to cities and giving the countryside little pockets of glow at night. They’re cheap to maintain, and owners of very small parcels of land appreciate them for their ability to bring in some easy income.

Running alongside these machines is a lower-tech tradition of mujin hanbai: farmers leaving vegetables in displays by the side of the road, with a suggested price for each item and an honesty box.

In the second part of this series next week, I’m going to look at how mujin hanbai, vending machine technology and convenience stores are being set up as part of the answer to Japan’s rapidly declining population. What started out centuries ago as a matter of trust and convenience may soon be a matter of survival.

I’ll leave you with two things. On the left, a brilliant image shared by a reader of this newsletter, featuring a wagyu beef vending machine handily situated next to a caviar machine. Both are ‘gacha’ style, meaning there’ll be an entertainingly random element to what you receive.

And on the right, possibly the creepiest vending machine I’ve ever seen, encountered at Kanda Myōjin shrine during a midnight walk around Tokyo earlier this year. It sells omikuji - traditional paper fortunes. But is this how you’d want to find out about your future?

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this essay, please hit the heart at the top of the page - it helps me understand what people are and aren’t enjoying.

If you loved the essay, then please consider helping to fund my next vending machine purchase via a subscription to this newsletter:

See you next week!

—

Images & video

Coca-Cola vending machine: Coca-Cola (fair use).

Tutti Frutti vending machine: Historic Towns of America (fair use).

Patent drawing: Yoshihiro Higuchi.

First vending machine in Japan: Postal Museum (fair use).

Essential Japan: Instagram (fair use).

Further reading

https://sts.kahaku.go.jp/diversity/document/system/pdf/026_e.pdf

My last visit to Tokyo was short: one shopping mall! On the lowest level, I was stopped cold by the array of vending machines. Of course, there were several animals figurine machines. The two my friends at home loved, though, were those vending freshly grilled steak next to chilled jars of caviar. If there had been some grilled veggies in the next vending machine, I could have gone for a fancy picnic in the nearby park!

I just went to the Oktoberfest in Yokohama and they sold wrist bands by vending machines, but it wasn’t very automated – you put your money in the machine as directed by a young woman standing there, and the machine produced a ticket which you then handed to her and she gave you the wrist bands. I guess sit just to avoid handling the money, as is done with ramen shops that you buy your meal ticket from a machine by the door.